It’s 2023. It’s a Tuesday. A glance at national news says that intercontinental spying is ratcheting up tension around the world. Record-breaking temperatures are recorded every day. Behind the headlines, there is a loneliness epidemic impacting every generation in modern America.

But fifteen years ago, the core of these fears were similar. The nation had entered into the Great Recession. Families fractured under economic pressure. Two wars were being fought abroad.

Yet one massive cultural difference between 2023 and 2008 is that fifteen-plus years ago, young people had a true outlet for their angst with their music. Much of that music fell into one bucket before siphoning into subgenres like screamo, alternative, hardcore, or post-hardcore: Emotional, or emo, music, with common themes centered on depression, self-harm, relationships, and loneliness.

Even then, what constituted emo music was slippery to define. But the mechanics were not technically new.

“Musically, it’s part-punk, part indie-rock, part singer-songwriter through a pretty pop filter,” Seattle-based songwriter and producer Jordani Sarreal told Chartmetric. “The common threads you’ll hear are the lyricism. It was a big deal.”

To Sarreal, the big difference between emo music and the rock that was on the radio in the early 2000s was that emo songs veered more introspective and poetic than their mainstream counterparts. A timeless track had small slices of lines that stuck with audiences after a single listen. For example, the clear opening lyrics of one of Taking Back Sunday’s first hits encapsulated this phenomena perfectly:

Your lipstick, his collar

Don't bother, angel

I know exactly what goes on

- Taking Back Sunday's "Cute Without the 'E'," 2002

Formulaically, these decipherable, sticky lines were dense and strung from verse to chorus to bridge. And even with the occasional screaming or growling, clear lyrics were at the core of any good emo song. That made the genre a sensation that audiences could scream along to without wondering if they were getting all of the lyrics just right.

Even for its popularity, many fans who were a part of the scene 15 to 20 years ago reflect on the time with a certain amount of cringe. Perhaps these mixed emotions are best exemplified by Spotify playlists with titles like kind of embarrassed, kind of jamming the fuck out and IT’S NOT A PHASE, MOM. But beneath the surface, there was a richness that cannot be so easily written off as teenage angst. The genre was holding a mirror up, more or less, on a larger, growing population of sensitive young people. In December 2021 Spencer Kornhaber wrote for The Atlantic: “Emo is not only a music of sadness—it is the music of change, uncertainty, and desperate, joyful connection.”

Plus, the genre bled beyond the confines of music. It was a culture. It was the scene. You learned about new bands from Myspace profile songs and from mixtapes that the friend with Limewire burned on your behalf. Emo had its own aesthetics, from skinny jeans to teased hair to immaculate liquid eyeliner drawn thick across the tops of eyelids. There were bulky digital cameras and photos with MySpace angles with the intention of distorting what those young people looked like online versus real life.

Another time frame similarly exemplified by aesthetic and fleeting, momentary trends was the hair metal of the 1980s. Hair metal followers were outcasts, more often than not, because they shirked conventionality, opted for gender-bending looks via hair and make-up, and embraced harder musical sounds than the reigning 1980s pop. The same parallels exemplified the energy of emo kids in 2005.

When one looks at a photo of a hair metal band in their prime, there is no question about the era they’re from, just as there is little confusion for millennials when they encounter photos of scene kids with neon raccoon steaks in their hair and checkered slip-on Vans on their feet.

But perhaps the largest parallel between the decades was the proliferation of one-hit wonders and bands that blended into the larger genre, but lacked originality. A band could enter into the trending emo or hair metal cannons with one single, but never make a truly distinct body of work and fade into oblivion.

This parallel between these former music trends was well-known, even in the early 2000s. In 2003, Brand New’s frontman Jesse Lacey noted for Spin that the emo genre was "becoming like Eighties hair metal all over again. All you can really do is try hard to be one of the bands that does manage to stick."

At its height, emo culture was best observed in live concerts, like the almighty Warped Tour, because youthful audiences approached their favorite bands as they would a deity or a God. A concert was a physical cleanse in the pushing and shoving of mosh pits where bodies thrashed in the shape of a cyclone. There were Walls of Death, the iconic moment where an audience split a venue down the middle, like Moses parting the Red Sea, until a breakdown of guitars indicated that it was time to turn and run in the opposite direction, like soldiers charging into war. Shoes were lost in the chaos and Craig Owens of Chiodos famously crowd-walked, something akin to walking on water, the devout balancing him in their hands as he rose above a musical pulpit.

For all of that commitment, one would think that emo momentum could be sustained forever, but it didn’t. The trend pittered out and effectively died out by around 2010. It’s not a genre that can sustain long-term, constant listening. It has a time and a place and teenage years are perhaps the most apt time for such a type of music to touch down, like a lightning strike across a dark field.

But that original emo fanbase is now adults in their late twenties to mid-thirties with disposable incomes, and festival organizers seem to recognize this – the iconic 2000s emo band the Used performed at Riot Fest 2023 in Chicago, along with Hawthorne Heights and Say Anything. It’s becoming increasingly clear that the genre is poised for a nostalgia-powered resurgence.

Riot Fest 2023 daily lineups are here. Get your 1-day, 2-day, or 3-day tickets now: https://t.co/BdIApfv7V6

— Riot Fest (@RiotFest) June 15, 2023

Details here - https://t.co/cXAHcQQT7I pic.twitter.com/z3xgXeWdks

Plus, it’s been about 20 years since emo music began in earnest, which means it’s poised to become a revitalized trend, like the 1990s and Y2K fashion have in recent years. As the 2020s continue, it’s only natural that younger generations are going to dig into what was popular for their parent’s generation and take it under their wing.

But can these bands capitalize on their historic fanbases in the way that the parents of emo kids supported their favorite hair metal bands as they got older? When a genre becomes a massive trend, what makes one band stand out from the crowd enough to command a long-term following? Who from the emo canon is doing so already?

Emo bands are still young compared to 1980s hair metal bands. The latter, at this juncture, has global listeners across generations. It may take another decade to know precisely how the original emo fanbase will keep interacting with the music and pass it along to their kids. But even now, geographical considerations reveal which bands may be slated to rise in popularity in the same way.

One point of reference for what a trendy, legacy fanbase looks like are hair metal bands Motley Crue and Def Leppard. At this point, neither are domestic phenomena: They’re global. Some of Motley Crue’s most active fanbases in terms of Spotify listenership and monthly YouTube views extend out of the English-speaking world and across Latin America to Mexico, Chile, and Colombia. Def Leppard captures the same countries through those metrics. In fact, both Motley Crue and Def Leppard have seen significant buoys in Spotify listenership in 2023 not from American audiences, but from fanbases in Mexico City.

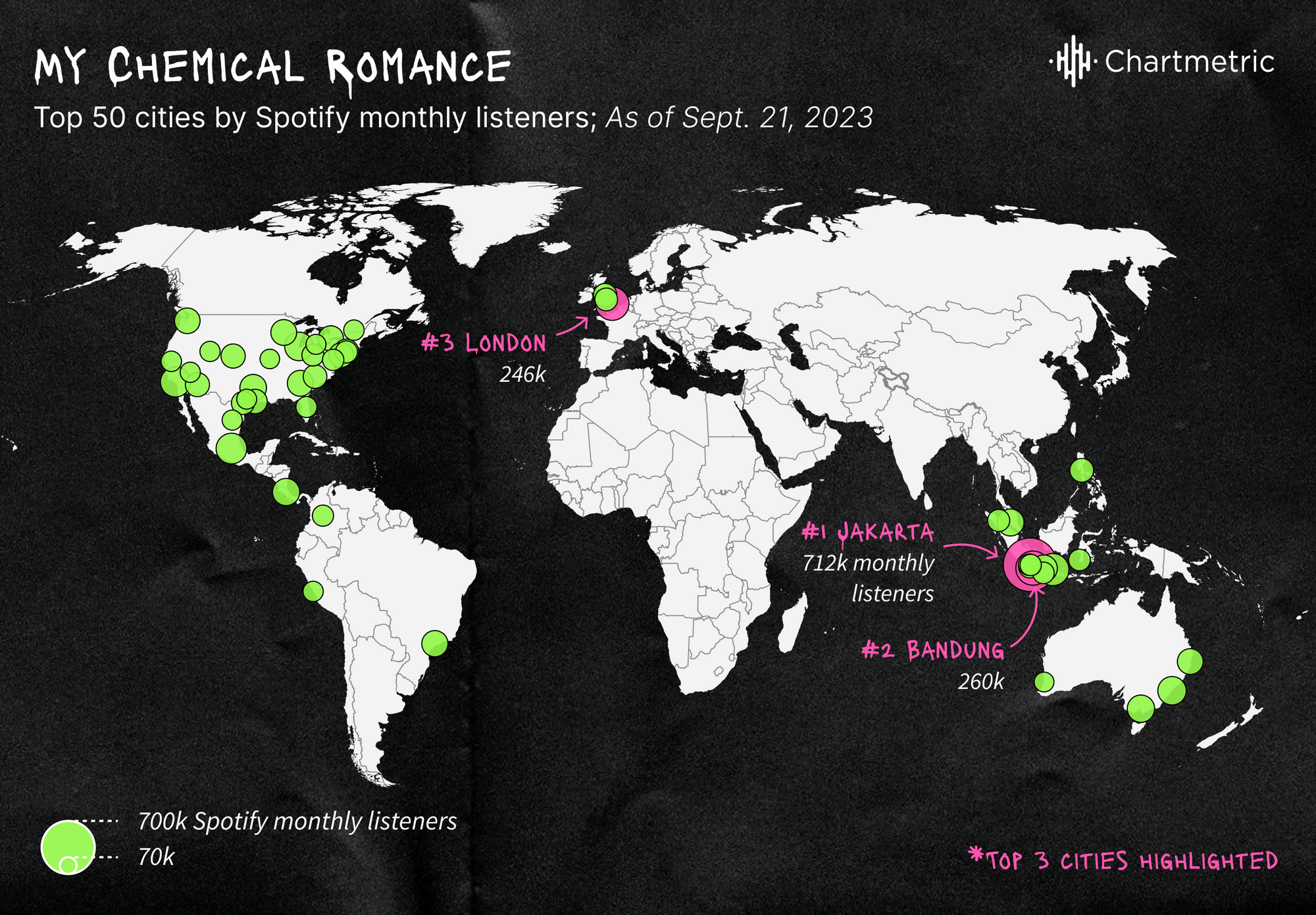

My Chemical Romance (MCR) is arguably one of the most famed emo bands that crossed into the mainstream psyche. Part of their popularity stemmed from being more theatrical in their approach than comparable bands at the time and, thus, more original. Now, MCR joins the ranks of Motley Crue and Def Leppard with a truly globalized audience that many other bands don’t have. For comparison, emo bands like Chiodos and Underoath have purely domestic audiences that don’t span outside of the country via Spotify or YouTube metrics. Indonesia, Mexico, and Malaysia are some of the top countries by Spotify listenership for MCR while Russia, Brazil, and Chile nab top spots via Instagram followers.

In Jakarta, Indonesia specifically, there has been a significant spike in listenership since mid-May 2023 that had MCR rambling towards one million listeners out of the city alone, four times that of Motley Crue’s or Def Leppard’s spikes over the past six months. When compared to the two legacy hair metal examples, MCR blows each out of the water.

Saosin is another example. Even for being a dormant band at this point in time, it is Jakarta that carries more monthly Spotify listeners from the city alone (60k) than the top domestic market for Hawthorne Heights and Brand New in Los Angeles combined, where each band has around 30k listeners per month. Thus, there is a considerable global appetite for an emo revival, not just in domestic or English-speaking audiences.

But beyond where audiences are, age is perhaps the biggest indicator of an upcoming emo revival. For example, Taking Back Sunday’s YouTube demographics are dominated by Gen Z listeners who were infants when “Cute Without the 'E'” and “You’re So Last Summer” came out. The Used also has incredibly strong Gen Z followings across YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. MCR’s core listenership is also female Gen Z listeners between 18–24 and millennials between 25–34.

Festivals beyond Riot Fest are now catching wind of the opportunities to share emo music with younger fans. Alternative music festival Bamboozle was resurrected in 2023 after a nearly decade–long hiatus with mid-2000s bands like Say Anything, Mayday Parade, and Boys Like Girls. Warped Tour, the iconic music festival that encompassed bands across the spectrum of the genre, shuttered after 20 years in 2018. But in 2022, a similar festival in Las Vegas titled When We Were Young launched with raving excitement. The festival looked eerily similar to Warped Tour in branding and spirit—and quickly sold out its tickets. The line-up was scattered with bands firmly in the scene of the mid-2000s, from MCR to The All-American Rejects to Dashboard Confessional.

suddenly I’m 15 again https://t.co/PSsYmxJUPu

— 𝔩𝔦𝔩 𝔰𝔱𝔬𝔫𝔢𝔶 🖤 (@deadgrrlfriend) January 20, 2022

However, the themes that drew listeners to emo music in the first place could drive a wedge between bands and their original fanbases. It’s hard to say if the same people in a Wall of Death at 15 years old will want to return to a concert and see that same band 20 years later with a kid, spouse, and mortgage waiting for them at home.

Plus, it gets harder to remain so earnest and so vulnerable as an adult. Bills need to be paid. Jobs need to be tended to. Most people cannot feel motivated to accomplish what they need to as adults surrounded by art centering on self-destruction and sadness. It’s arguable that emo music may rescind into memory for a substantial portion of the aging fanbase without continual engagement.

But the revival is coming. The tours are being planned. The bands are getting booked. Only time will tell if emo music will return in full swing, rising from the ashes, to prove just about everyone wrong.

“If I think about who is still playing music and still in this conversation 15 years later, those were my favorite bands out of this genre,” notes Sarreal. “They were the popiest ones, they had the best lyrics and the best melodies, and they happen to be the ones that are still touring.”

Graphics by Nicki Camberg and cover image by Crasianne Tirado; data as of Sept. 25, 2023.