The jury’s still out on whether or not a robot can write a symphony, but when it comes to a three-minute song to play in the background, AI is nearly indistinguishable from the real thing.

This truth was recently proven by The Velvet Sundown, a throwback indie rock group who quickly amassed hundreds of thousands of listeners on Spotify with songs like “Dust on the Wind." Their tracks are styled after classic 70s songs and pleasant enough to blend into mixes of classic Americana or evocative genre playlists like “Vietnam War Music” or “Woodstock Festival 69.” There’s just one twist — the whole project, music, vocals, lyrics, and all, was generated on the AI music platform Suno.

As adept as The Velvet Sundown’s generation and marketing have been, the project’s fictitious nature isn’t exactly inconspicuous. Even before they admitted to their AI background, a cursory look through the band’s profile shows all the classic hallmarks of AI composition — a too-perfect band portrait and non-specific bio chief among them. However, the songs on the albums that launched The Velvet Sundown to fame, Floating on Echoes and Dust and Silence, are catchy, pleasant, and evocative enough that they can easily blend into playlists filled with traditional artists.

The Velvet Sundown is far from the first “fictitious” group to gain a significant streaming presence by offering comforting background music to populate playlists. In fact, many have noticed that several of the ambient, classical, and mood-music playlists curated by streaming services are populated not by famous musicians but so-called “ghost artists.”

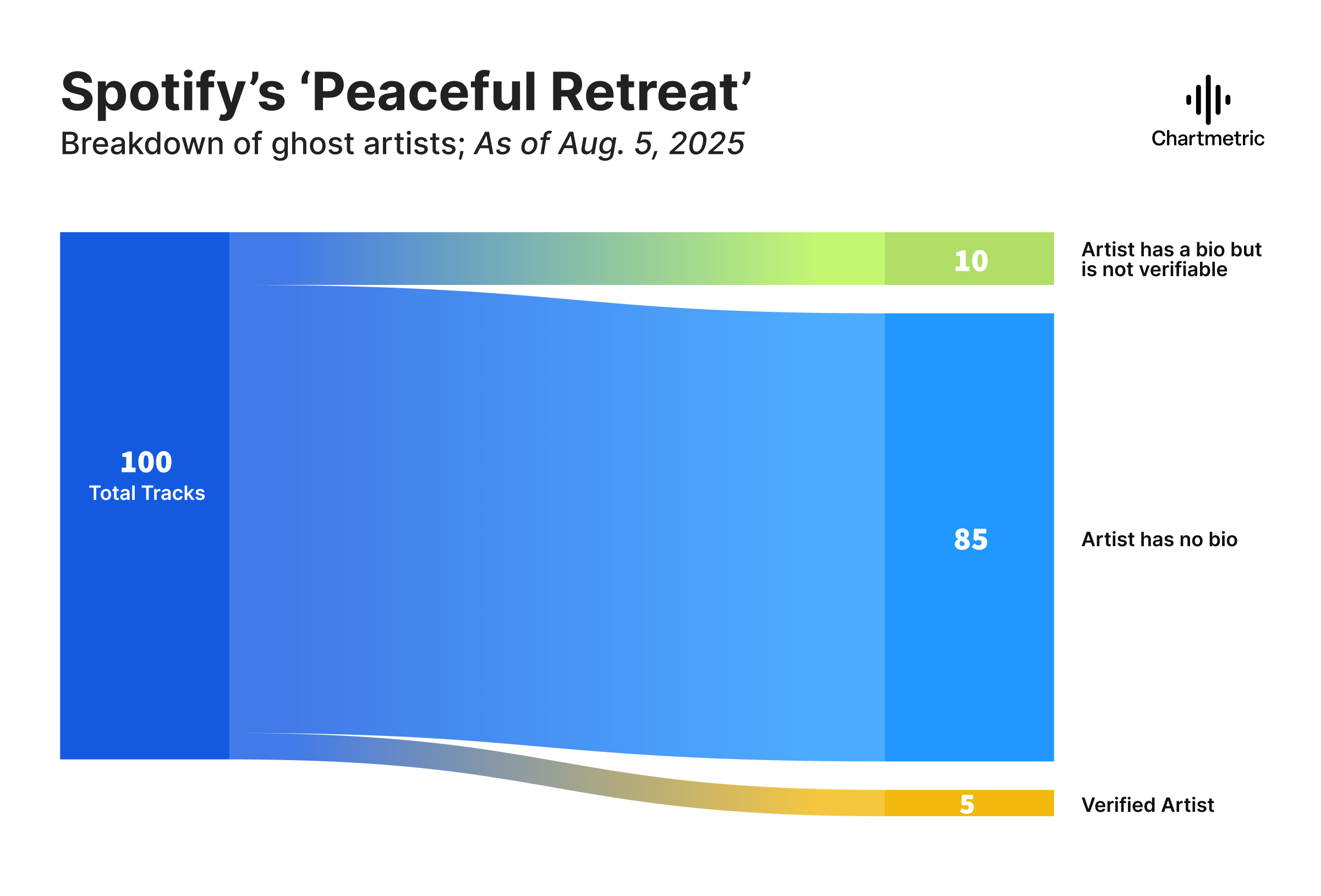

Take Peaceful Retreat, a Spotify-curated playlist of calming background music. In a sample of 100 of the playlist’s tracks, 85 are credited to artists whose profiles are verified, but lack bios, links, or any evidence of media presence outside of streaming platforms.

Of the 15 remaining artists who actually have something other than blank space in their bio sections, most have simple descriptions of their music, but again, no link back to a specific human presence. Only five artists out of 100 featured in Peaceful Retreat can directly be traced back to real human sources who take credit for their tracks — like Nebula Somni and Volta Celeste, which both turn out to be ambient side projects of the (very real) Italian composer Giandomenico “Domy” Castellano. But while Castellano posts online about his journey to getting featured on editorial playlists, the stories behind these 85 other bio-less artists are more mysterious.

So what’s the deal? Are these “ghost artists” AI-generated projects like The Velvet Sundown? Experimental pseudonymous content? Sentient spawn of the algorithm?

The answer mixes all of the above.

What Is Perfect Fit Content?

According to journalist Liz Pelly’s book Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Perfect Playlist, published earlier this year by Simon and Schuster, these ghost artists don’t just spring up out of nowhere. Instead, they are part of a content strategy developed by streaming services to create music specifically to serve certain moods, well, perfectly. Spotify called their program Perfect Fit Content, or PFC, and the name has stuck.

Usually, PFC is commissioned directly by streaming platforms or affiliated production companies to fill playlists aimed toward a certain mood or emotional experience. Rather than licensing existing music, companies hire composers and producers, who then create and perform tracks according to specific prompts — a popular side gig for music students.

These recordings are then credited to verified artist profiles with fictional names that feel appropriate for the music, which then end up on playlists with names like “Focus,” “Chill” or “Ambient”.

Fortunately for fans of the ambient genre, however, Spotify and other streaming services often keep genre-driven playlists filled with name artists — playlists like “New Ambient” or “Classic Ambient” — separate from the mood playlists, allowing listeners to generally choose between their style of ambience.

The musical ecosystem on streaming services now exists in two distinct layers: playlists that focus on ambient as a genre, and playlists that focus on creating ambience as a functional goal.

The Man of 600 Names

The PFC process employs plenty of student artists and aspiring musicians, but some of the medium’s biggest influences are individual composers who publish under dozens — or even hundreds — of different names.

If you came across the artists Mingmei Hsueh, Csizmazia Etel, and Maya Åström on a playlist, you might picture multiple distinct people of different ethnicities and genders. However (like a lot of pop music) they are in actuality the product of a single Swedish man.

According to Swedish publication Dagens Nyheter, these are just some of the aliases of Johan Röhr, a composer who has become one of the most prolific PFC creators, racking up streams by publishing songs under nearly 650 aliases.

This strategy works. Some of ambient music’s influential contemporary figures, like Tim Hecker, James Holden, and William Basinski, have had breakthrough songs that rack up multi-million plays on Spotify — for example, Basinski’s “Melancholia II” has more than 14 million. But Röhr’s streaming accomplishments dwarf even the most successful songs by regular ambient artists. According to DN, Röhr’s 2,700 different compositions have been streamed more than 15 billion times total — more than Britney Spears, Abba, and Blackpink — and nearly 15 times as many as the total plays for ambient music’s biggest artist, Aphex Twin.

Even though other ambient composers have greater influence and followings outside of the streaming world, Röhr’s position as a main man behind PFC makes him one of the genre’s dominant forces on Spotify, showing that there are multiple ways to succeed in the world of mood music.

Figge and the Catfish Catalog

Rohr isn’t the only Swedish musician who is responsible for a huge number of ambient music projects. Frederik “Figge” Boström is a veteran musician who is credited as a bass player for British pop acts, a producer for K-pop groups, and even as a co-writer for a song that made it to the Eurovision grand final.

Though his history is in pop music, Boström leveraged his behind-the-scenes musical experience and skill set to pivot to mood music, launching his company Catfish Music Group, which, according to its website, represents piano-based artists in the ambient and classical space.

However, while the label’s “about us” section claims to represent artists “Ana Olgica, Samuel Lindon, Bela Nemeth, Evelyn Stein, Martin Fox, Joszef Gatysik, Julius Aston, Max Swan, Sub-City Keys, Cadet de l’espace, Tomasz Kraal, Koral Banko and many more,” these artists themselves appear to be of what one might call “dubious reality.”

Of the artists listed, only Ana Olgica has any evidence of being a real human outside the world of Spotify playlists. A third-party blog post by someone who claims to know her well discusses Ana Olgica as an artist — though the comments section casts doubt on whether this piece is real or fictional. However, when it comes to the other artists on the Catfish Music roster, they appear to only exist on streaming services, and BMI and ASCAP data shows that Boström is credited as writer and producer for all of their tracks. Even if there are “real” artists on the Catfish roster, it appears that several are really Boström himself in disguise, playfully publishing his own compositions under false names — or “Catfish”ing.

In terms of reach, PFC has been a boon to Boström. Even though he has written and played on some bona fide hit songs, even his Eurovision final entry lacks the streaming impact of his PFC music. In 2012, Boström co-wrote Norway’s Eurovision entry, “Stay” by Tooji, which made it all the way to the grand final — before finishing in last place with seven votes. “Stay” has racked up more than five million plays on Spotify, but each of the aliases that Bostrom promotes on Catfish Music has a song with more plays than this.

PFC and the AI Future

Detractors may argue that the prompt-driven music of PFC and The Velvet Sundown can take the human element out of the modern music industry. However, audiences have shown a genuine connection to the music on display here, proving that the music can connect.

Even though the artist Samuel Lindon is really Figge Boström in disguise, his song “Tallis One” has become popular enough as mood music that fans upload piano tutorials and YouTube covers, even creating sheet music for actual live performers to play it on their own. The biggest song by The Velvet Sundown, “Dust on the Wind” is the subject of a YouTube cover by a very real bassist. Even without intending it, this “fake” music has an impact on the real lives of listeners and fellow musicians. Some even use it as a jumping-off point for their own art.

In 2018, Fred Rocha, a Portuguese website developer and music student, started noticing the ghost artists and their mysterious lack of background. He built ghostmusician.com, a website that takes these fake artists and gives them fictional biographies and backgrounds — essentially, fleshing out these made-up PFC personae into real people.

“I guess it’s just how the creative process works,” Rocha says. “I was like ‘these guys don’t exist. Do they have a personality? Do they have a biography? Where did they attend music lessons? What’s their label?’ And I thought, yeah, no artists should be without a home, in a way.”

Rocha ended up writing bios for some of Röhr’s and Boström’s “ghost artist” personae, describing PFC alter egos like Piotr Miteska as “a special breed of musician” — which is true, in its own way.

Rocha stopped updating ghostmusician.com a few years ago, before Pelly’s reporting made the PFC project public. But in the intervening time, he has continued to pursue his own unique online music projects in an ever-growing attempt to curate compelling art.

“Good art is a lot about curation,” Rocha says. “Good curation is not only gathering stuff, but also doing it and showing it out in an intelligent language, a sensible way. So art is not just creating, but displaying.”

It’s this question of curation that poses the biggest challenge to the future of AI generation and PFC. As seen above, both AI bands like The Velvet Sundown and PFC artists like Rocha and Boström have had major success on streaming. However, they have done so under the guise of being “real artists” — even if the truth isn’t that hard to find. In reality, it's likely that AI music isn't going anywhere, and there are signs that prompt-driven music connects with audiences, but will listeners feel misled? With an interface that clearly labels ghost artists and AI-generated music, streaming services could give audiences the information they need to find the music they like — and engage in the kind of thoughtful curation that makes a playlist into a work of art.